Adolf Wölfli: psychotic inmate, mental patient, and artist

A violent schizophrenic and one of the most famous outsider artists

Adolf Wölfli was a Swiss inmate and mental patient who is one of the most celebrated outsider artists. A self-taught visionary, Wölfli spent most of his adult life institutionalized due to schizophrenia and violent behavior. Yet, within the confines of the asylum, he created an extraordinary and prolific body of work.

Born in 1864 in Bowil, Switzerland, Wölfli was the youngest of seven children. His parents struggled with poverty, and he endured physical and sexual abuse. Orphaned before the age of ten, he became a ward of the state, living in a series of foster homes.

In 1890, Wölfli was sentenced to two years in prison for the attempted molestation of two girls. Five years later, after another alleged incident, he was diagnosed with schizophrenia and committed to the Waldau Psychiatric Clinic in Bern, where he remained until he died in 1930.

Wölfli suffered from severe psychosis, terrifying hallucinations, and intense and violent rage. Physically dangerous, he was placed in solitary confinement for years.

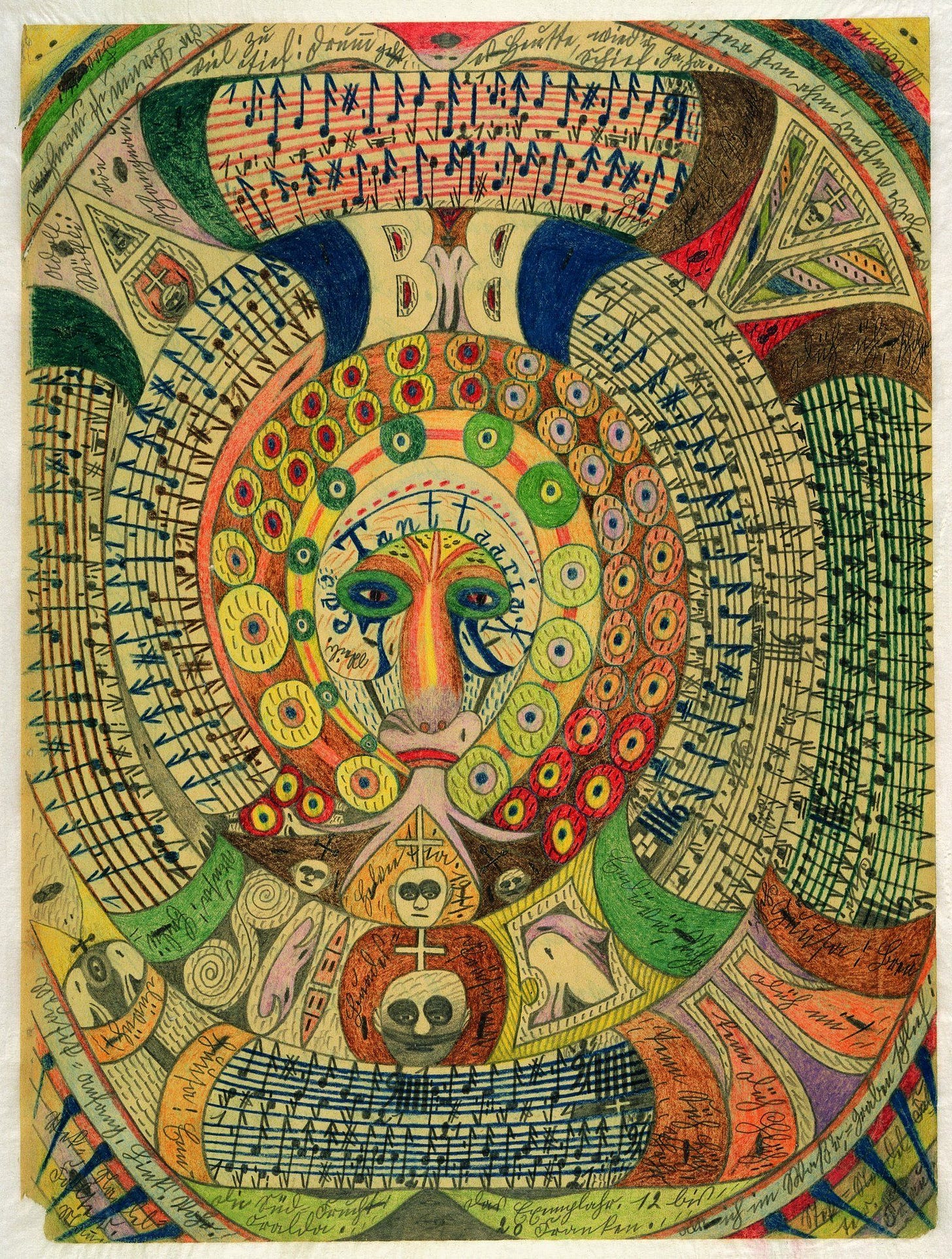

However, doctors observed that providing him with pencils and paper had a calming effect. He began to draw, write, compose music, and create collages. His earliest preserved works, dating from 1904, feature highly detailed, symmetrical pencil lines on newsprint. These early pieces incorporated images, words, and musical notations, foreshadowing the motifs and symbols that would define his later creations.

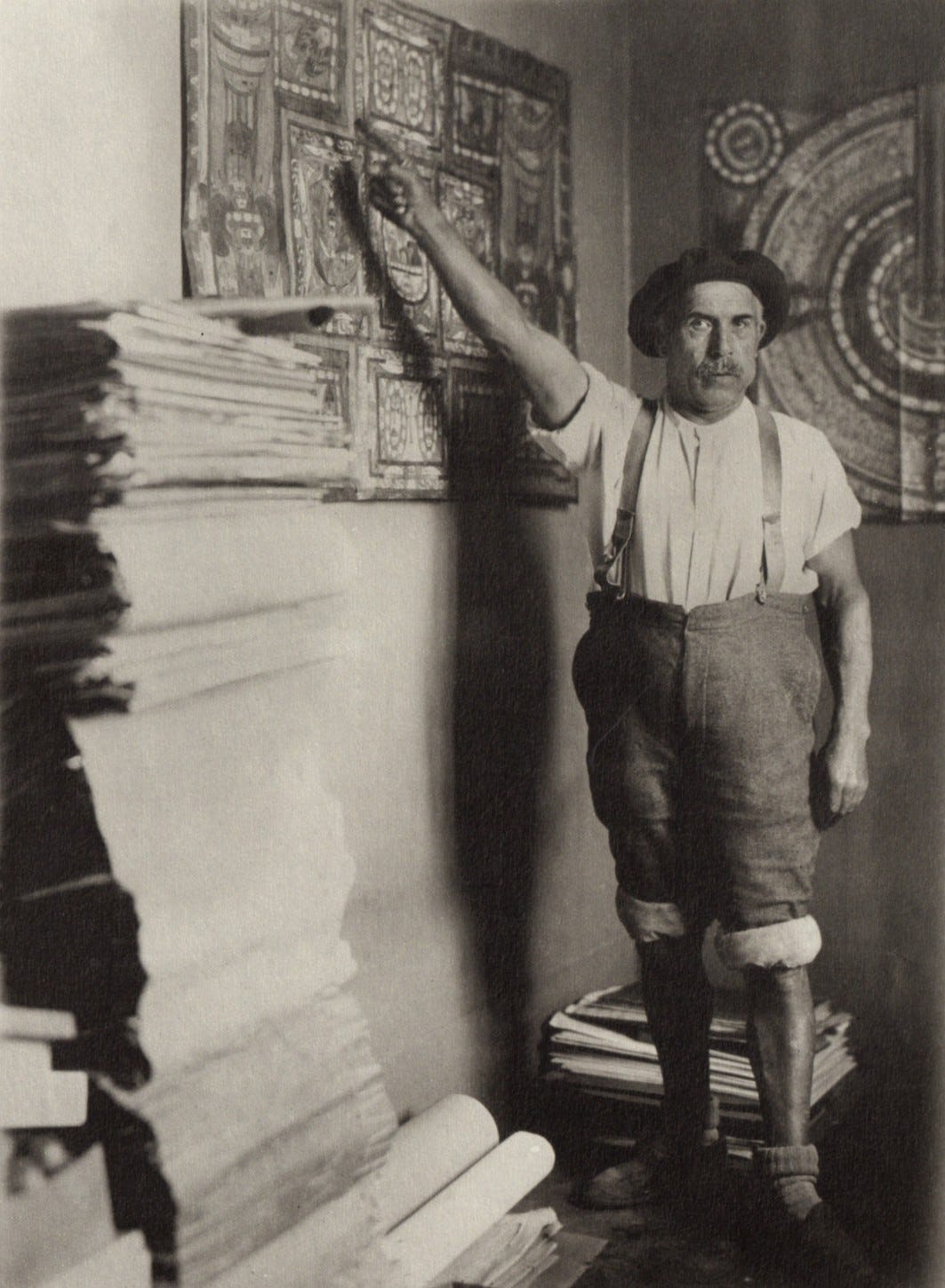

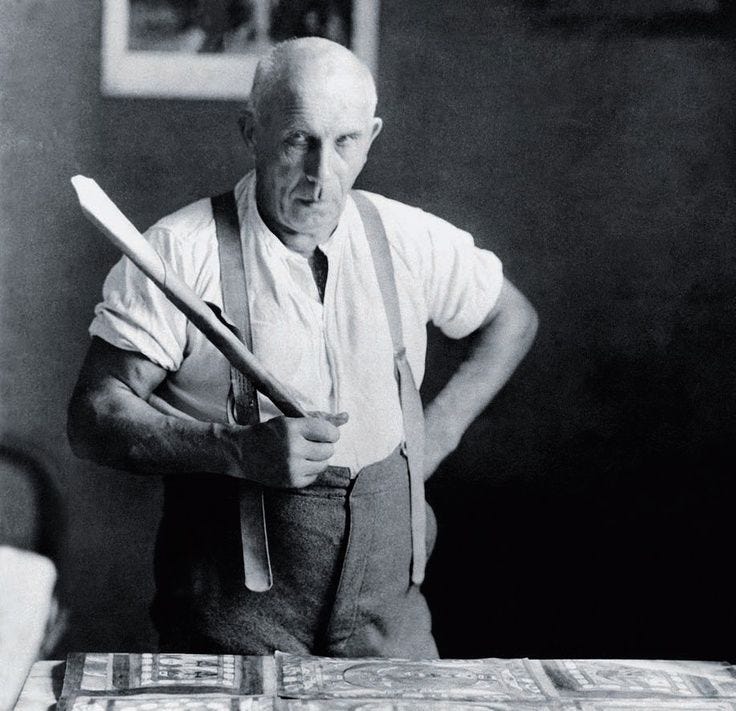

Dr. Walter Morgenthaler, a psychiatrist who arrived at Waldau in 1908, became a crucial supporter in Wölfli's artistic life. That same year, Wölfli began an epic autobiographical project that would consume the remaining twenty-two years of his life. This vast text, interwoven with poetry, musical compositions, and three thousand illustrations, spanned over twenty-five thousand pages. Within these volumes, he recast himself as a sainted child, reimagining his life in fantastical terms. Hand-bound and stacked in his cell, his forty-five volumes eventually reached a height of over six feet.

Morgenthaler documented Wölfli's creative process, noting how he worked with minimal materials. Wölfli received a new pencil and two large sheets of unprinted newsprint every Monday. Within two days, the pencil was reduced to a stub, forcing him to scavenge for scraps and trade artwork to visitors for supplies.

Wölfli’s intricate, highly detailed images filled every inch of the page, a style described as "horror vacui"—a fear of empty space. Among his signature motifs were small holes surrounded by shapes he called "birds."

His work also incorporated a unique musical notation, initially decorative but later evolving into real compositions that he played on a paper trumpet.

Shortly before his death, Wölfli lamented that he could not complete the final section of his autobiography—a monumental finale titled Funeral March, which comprised nearly three thousand songs.

His work gained recognition through the advocacy of artist Jean Dubuffet and Morgenthaler’s 1921 book, A Mental Patient as Artist.

This is so fascinating. I wonder if anyone has tried to play through his music on a piano. I think his story would make an amazing operetta or musical. Kind of like John Adams' "Dr. Atomic". Haunting.