Art is, at its core, a human construct. There is no single, objective definition, and what counts as art ultimately depends on the beholder. As with spirituality and mysticism, it is an emotional, intuitive, and subconscious experience, something that cannot be fully captured in words or conscious intellectualization. Trying to pin it down into a rigid definition is a fool’s errand and defies what it is.

Many early and popular definitions of art insist that it must be beautiful. Beauty has often been treated as the standard by which art is judged. But should that be the case? Does art lose its status if it is unsettling, strange, and ugly, or might these qualities be just as essential to its power and purpose?

While anyone is free to define art in their own way, definitions carry consequences. Restricting art to what is conventionally beautiful or morally uplifting excludes much of what makes creativity meaningful, such as experiences of awe, wonder, discomfort, moral reflection, and shock. A narrow definition not only leaves these dimensions outside its scope but also diminishes art’s philosophical and speculative potential. If we insist that art must be only beautiful and virtuous, we are forced to invent another category to contain the vast range of expression that such limits leave out.

In many cases, the term sublime is more fitting than beauty. Often but not always including beautiful things, sublimity captures what is transcendent, transformative, and mind-expanding, even when it is unsettling, discordant, or ugly. Art that challenges our conventions can lift us beyond the familiar and open us to deeper insights.

Art is rooted in human evolution. Our brains evolved to detect patterns, symmetry, and harmony. However, from an evolutionary standpoint, aesthetics are not limited to beauty and love. They also encompass repulsion, danger, chaos, fear, and anger, responses that were just as essential for survival. These abilities once helped our ancestors spot threats, locate resources, attract mates, and navigate social life.

Art focuses on these instincts, turning them into exploration expressed through the language of emotion, subconscious intuition, cognitive biases, and aesthetic taste. It is a particular way of thinking, and ordering and analyzing information. Psychologist and art theorist Rudolf Arnheim emphasized that sensory perception is itself a form of thinking. For Arnheim, sensing is never a passive act. It is an active, cognitive process that shapes understanding.

Even if one defines art as beautiful, the definition of beauty is itself a can of worms. What initially seems ugly may simply be unfamiliar. Over time, exposure and reflection allow the mind to uncover complexity, hidden beauty, and profound meaning.

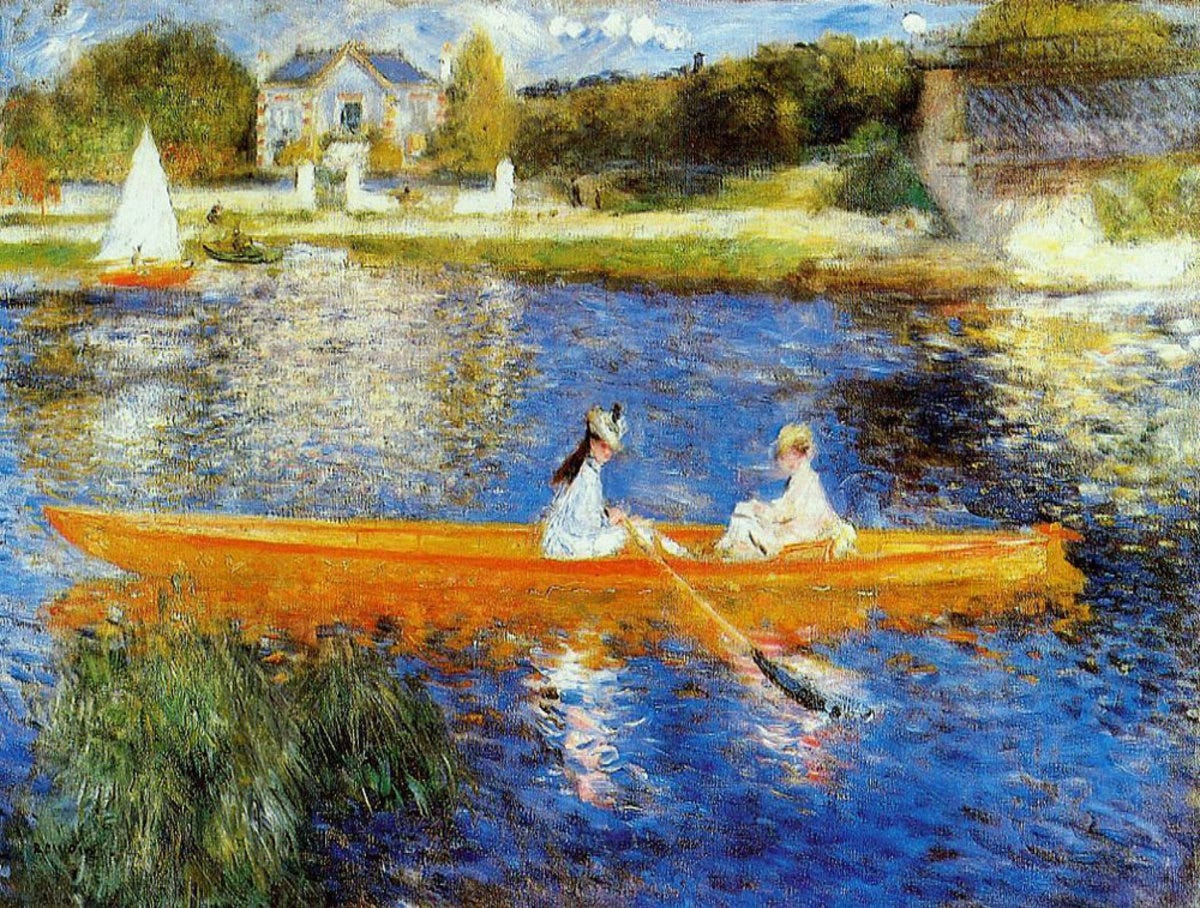

Beauty and ugliness are often cultural and subjective. What one society or generation finds ugly, another may revere. Stravinsky and Prokofiev were initially criticized for harshness. Renoir, Van Gogh, and the Impressionists were dismissed as ugly and amateurish. Beethoven’s Third Symphony was considered immoral and not performed until after his death. Across cultures, African masks, Japanese prints, and aboriginal designs were often deemed primitive, yet they reveal sophisticated patterns, symbolism, and craft.

Pablo Picasso and Marcel Duchamp provide examples of how art can move outside of beauty.

Picasso said he wasn’t always trying to make a work that was beautiful. His focus was often on other qualities, and he considered the expected cliched commentaries about the work’s beauty, or lack thereof, to be missing the point.

Many of his cubist works were trying to depict three dimensions in a two-dimensional plane, an aesthetic and philosophical dilemma that exists in all two-dimensional artworks. Some of his cubist works tried to depict the passage of time in a still image, another interesting and unsolvable aesthetics problem that exists in all still art, even so-called realistic art.

Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917), an ordinary urinal turned on its side and signed “R. Mutt,” was a provocative challenge to traditional ideas of art. By presenting a mass-produced object as art, Duchamp argued that creativity lies in the artist’s choice and concept rather than in craftsmanship or beauty. This “readymade” questioned the authority of art institutions, shifted focus from object to idea, and mocked the seriousness of aesthetic tradition with humor and irony. In doing so, it opened the door for conceptual art and forced audiences to reconsider the very definition of art.

If one looks at a Picasso or Duchamp work as a philosophical examination, the question of “Is it beautiful or not?” becomes “Is whether or not it’s beautiful a relevant question?”

Edvard Munch’s The Scream, Francis Bacon’s paintings, and Hubert Selby Jr.’s novels, were exploring not beauty or joy, but inner torment, anxiety, and angst, and the restraints of societal norms and expectations.

A Brooklyn heroin addict who nearly died turned devout Christian, Selby Jr. wrote what he saw as religious morality tales about New York City's lost people of the 1950s-70s: homeless, criminals, drug addicts, prostitutes, mentally ill, and sexual outcasts. His novels, including Last Exit to Brooklyn, The Room, and Requiem for a Dream, are highly acclaimed and considered revolutionary in their writing style, but also considered among the most disturbing ever written. Selby said, "What I attempt to do is go as deeply into the darkness of the human soul as possible and then hopefully come back."

Dismissing Munch’s, Bacon’s, and Selby’s works as “unbeautiful” misses their point and their purpose.

Ultimately, art should encompass the full range of human emotion and experience, from the beautiful to the profoundly dark. It can be ugly, and in that very ugliness, it can become sublime. Art is a medium for exploring aesthetics, philosophy, emotion, and perception. Beauty is only one facet of this spectrum.

You're right, David, art conveys.

I liked Jimi Hendrix's anguished national anthem at Woodstock. It fit the times.

Shook me to see "Last Exit to Brooklyn" on your list. I thought it was unknown. It shook me more when I saw the movie decades ago. No tenderness. Only alienated loneliness. It fit the times. The movie "Monster" had a similar tone.

Another little-known but telling book of stupidity and cruelty: Jerzy Kosinski's "Painted Bird."

Finally, the warning novel that became, unfortunately, a how-to: "1984."

Thanks! Very thought-provoking.