Cognitive and neurological influences behind beliefs in god

Neuroscience influences one's worldview.

There are various innate cognitive and neurological processes that shape people's beliefs in and conceptions of God or a higher religious power. These beliefs, and the ways they are described, stem from unconscious psychological tendencies that humans have developed to function and survive as a species.

The human brain is inherently wired to create meaning. We constantly seek out patterns, purpose, motives, and cause-and-effect relationships in our surroundings. These tendencies play a key role in the formation of religious and spiritual beliefs. Just as we search for meaning and patterns in a room, a photograph, or an abstract painting, we do the same when contemplating the universe and the unknown.

Below are some cognitive processes that contribute to the development of religious beliefs.

The Search and Desire for Order

Humans have a natural tendency to seek order, whether in their daily lives or in the face of chaotic or ambiguous situations. This drive to identify patterns and impose structure is essential for functioning and survival.

This desire for order extends to how people perceive the unknowable aspects of the universe and reality. Many people not only seek order in the universe but also imagine and impose it, creating a sense of structure where none may be apparent. This inclination influences beliefs in God, a higher power, or an orderly universe. Even non-theists and scientists often assume that the universe operates under a set of structured principles, even though it is impossible to definitively prove such order exists. And if the universe is ordered, it may be in ways beyond human understanding or perception.

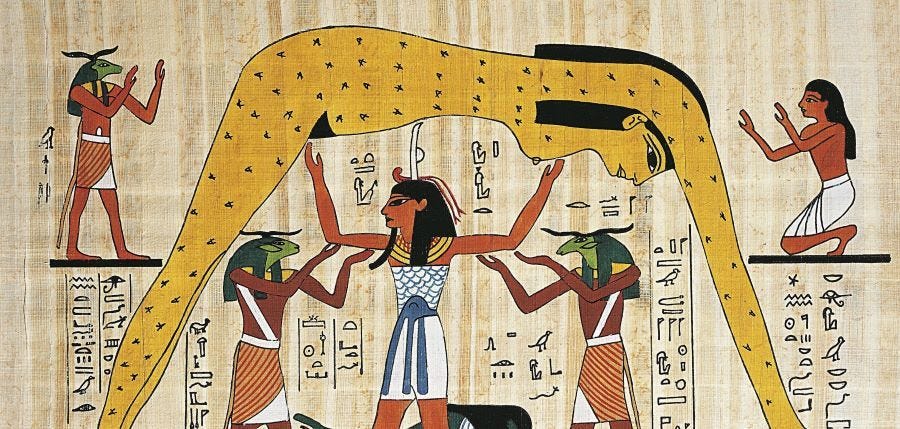

In certain religions, the concept of God is tied to the idea of bringing order out of chaos. For example, the ancient Egyptians believed that the god Atum created the earth and its principles from chaos and darkness. They saw it as their duty to live moral, ethical lives to keep chaos at bay.

A common religious belief is that moral order originates from God or a higher power. As a result, some believers argue that without belief in God, an atheist cannot have a moral foundation.

The Innate tendency to Perceive Meaning and Purpose Behind Things and Events

Humans have an innate tendency to seek meaning and purpose in the world around them. Just as we search for patterns, this instinct has been crucial for human survival and functioning.

Understanding the purpose behind events, groups of people, or even animals plays an essential role in social survival. For instance, if a group of people or dogs approaches you, your instinct is to try to guess their intentions. Similarly, if you hear a loud noise in your house at night, your mind immediately assumes there is a cause behind it. This tendency to assume the worst helps ensure safety and self-preservation, which is why many people will get out of bed to check for intruders. Our ancestors would not have survived without this inclination to err on the side of caution.

In her paper, Why Are Rocks Pointy? Children’s Preference for Teleological Explanations of the Natural World, Boston University psychology professor Deborah Kelemen explains how children often assign purpose where none exists. For example, when asked why a group of rocks is pointy, children might say it’s to prevent animals from sitting on them. Similarly, they might suggest that rivers exist so humans can fish in them. These explanations reflect a natural tendency to assign purpose and meaning based on human logic and expectations, often centering around human needs.

Kelemen argues that this bias in children allows them to easily conceive of a being who created the universe with a specific purpose. This same cognitive tendency persists in many adults.

Humans Perceive Minds Beyond Their Own

Humans have the unique ability to perceive that others possess minds, which is vital for social functioning and the survival of the species. As social animals, we rely on our ability to interpret the thoughts and intentions of both humans and non-human animals.

Humans don’t just attribute minds to other living beings—they often project mental states onto inanimate objects. Whether it's teddy bears, dolls, toys, cars, or figures in artworks, we frequently imagine these objects as having thoughts or emotions. We readily accept cartoon characters that talk and think, even when they are depicted as cars, toasters, or trees. People even find themselves speaking to paintings or wondering about the thoughts and actions of the subjects they depict.

This tendency to imagine minds in non-living things extends to how people perceive nature and the universe, often contributing to the formation of beliefs in God or a higher power. Some people, both religious and non-religious, conceive of nature, plants, or even the universe as having a kind of consciousness. In fact, when scientists and philosophers discuss the consciousness of the planet or the universe, they come close to notions that resemble belief in a divine entity.

Anthropomorphism

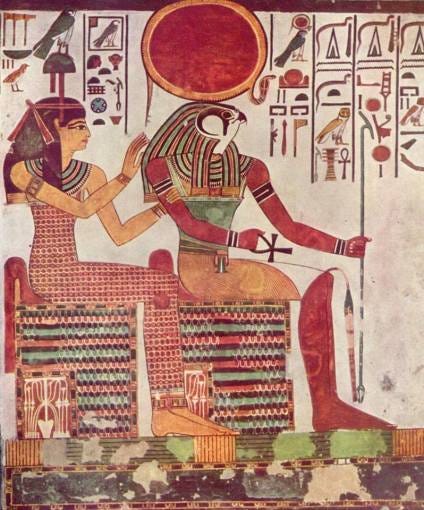

Humans naturally tend to attribute human thoughts and emotions to non-human entities. We often mistakenly assume that animals think and feel as we do, interpreting their reactions through a human lens. This extends to how we create non-human cartoon characters that behave like people, see human faces in abstract shapes, and describe inanimate objects or natural forces using human terms—like "Mother Earth" or "Father Time." Given this, it's not surprising that humans imagine the unseen reality of the universe as a sentient being and depict gods or deities in human-like forms with human thoughts, motives, and ideas.

Similarly, humans often attribute animal qualities to non-animal entities. We describe the "howl" of the wind or speak of "the hound of love," and many gods and deities are depicted in animal forms.

While anthropomorphism is not always meant to be taken literally, it serves as a symbolic way for humans to interpret the world. This tendency reflects how we view and translate everything—even nature, random information, and the unknowable—through a human lens.

Humans Perceive the World Emotionally

Emotions and aesthetics are deeply ingrained in human perception, judgment, and thought processes. We instinctively and automatically make emotional judgments about new experiences, strangers, unfamiliar objects, and even facts. These emotional responses influence how we describe non-human things, often in terms that evoke human emotions: "universal love," "the angry sea," "cruel fate," or "the happy sun."

Because people imagine the universe in emotional terms, it’s natural for them to conceive of the transcendent or the unknown in ways that are not only human-like but emotionally relatable. Human emotions shape how we understand and define the universe, bringing us closer to seeing it as a living, emotional being. For humans, the meaning of life and the universe is often tied to mood and emotion.

Humans Naturally Apply Narratives to Their Perceptions

Just as humans seek meaning, motives, and patterns in ambiguous information, we also instinctively interpret objects, scenes, or even snapshots of people as part of an unfolding story or narrative. This tendency reflects how we understand cause and effect, as well as our perception of time, meaning, and purpose. We even impose narratives on abstract information, creating stories to make sense of it.

This storytelling impulse extends to our interpretations of the universe and the unknown. We often frame these vast, incomprehensible concepts in human terms, applying narratives to them. Religious scriptures, for example, are presented as stories. The Christian Bible has even been called “The Greatest Story Ever Told.”

Religious Symbols and Texts as Figurative Translations

Depictions of gods, religious stories, and ceremonies are human interpretations of abstract ideas, designed for teaching, understanding, and communication. Theologically learned individuals understand these depictions are symbolic translations of concepts beyond human comprehension.

Just as teaching must be done in a language students can understand, religious teachings use metaphors and parables. Jesus taught in parables, while Buddha used riddles. The Christian “Kingdom of God” does not refer to a physical place but to a state of spiritual enlightenment. Hindus use deities to represent aspects of transcendent reality because literal depictions would be too complex for the human mind. As a Hindu student becomes more knowledgeable, their understanding of the divine grows more intricate.

Even figures like Jesus are seen as metaphors, at least in how they are portrayed in religious contexts.

Some atheists and anti-theists make the mistake of mocking religious beliefs as literal, but this misunderstanding overlooks the symbolic nature of religious teachings. Learned Christians do not literally believe God is an old man with a white beard on a throne, and learned Hindus do not believe in thousands of individual gods. These depictions are symbolic ways of communicating deeper truths.

Thinking Styles Influence Beliefs

The way people think affects their beliefs. Those who rely on emotions and intuition, or "gut feelings," are more likely to believe in God or a higher power. When their intuitive reactions are often correct, they tend to trust the cognitive tendencies discussed earlier, making them more likely to believe in magic, the paranormal, or God.

On the other hand, people who approach things logically, especially those whose intuition has been proven wrong in the past, are less likely to believe in a deity. They learn to question their cognitive biases and consider alternative possibilities, developing a habit of critically examining their innate tendencies.

Steve Novella MD, Professor of Neurology at Yale University, puts it: "It is the standard skeptical narrative that people are biased in numerous ways. The default mode of human behavior is to drift along with our cognitive biases unless we develop critical thinking skills. Metacognition—thinking about thinking—is the only way our higher cognitive function (evidence, analysis, logic) can take control of our beliefs from our baser instincts."

Conscious Motivations for Belief

People often believe in God or higher powers for conscious, calculated reasons. Some are uncomfortable with chaos and seek answers, while others desire a sense of purpose, fear death, or like the idea of universal justice. Belief can also be a way of coping with loss or suffering. For many, faith simply makes them feel better.

Social pressures also play a role. Many people adopt religious beliefs to fit into a theistic culture or community. Religious practices are deeply embedded in many cultures, and for some, being part of a religious group is as much about belonging to a community as it is about spiritual belief.

Social Order and Shared Beliefs

Shared beliefs and a sense of purpose are crucial for maintaining social cohesion. Many societies throughout history have relied on belief in God or higher powers to keep groups united. Just as games need rules, even if arbitrary, belief in a deity has often served to provide those rules. Leaders throughout history have claimed divine status or a special connection to a higher power to maintain authority.

As Steve Taylor, a psychology lecturer at Leeds Beckett University, notes: "Dogmatic religion stems from a psychological need for group identity and belonging, along with a need for certainty and meaning. Humans have a strong impulse to define themselves—whether as a Christian, Muslim, American, or even a fan of a sports team. This impulse is tied to the desire to belong to a group and share the same beliefs as others. At the same time, there’s a need for certainty, the feeling that you possess the truth and are right while others are wrong."

Perception of the Universe in Human Terms

In the end, humans can only perceive, conceptualize, and describe things through the lens of their own biases, logic, biology, and senses. As a result, the universe and abstract concepts are often interpreted in human ways, with human-like qualities, stories, and motives. This is true not only for religious believers but also for many non-religious individuals, even if they don’t invoke a deity.

These Cognitive Processes Do Not Prove or Disprove God

Some may argue that these psychological tendencies prove that God is merely a product of the human mind, but this is not the case. While these processes show that religious beliefs are shaped in part by human psychology, they neither prove nor disprove the existence of God or a higher power.