Is Objectivity Possible?

A cognitive and neuroscience perspective

Preface: This post was inspired by a forum discussion where someone asked for an unbiased news source to follow. Most people responded that truly unbiased news doesn't exist. Instead, they recommended reading a variety of sources to gain a fuller understanding and see different perspectives on the same story. It was pointed out that, even when the reporting on a particular topic seems neutral, outlets still choose which topics to cover, which introduces bias. For this reason alone, it's essential to read across a range of sources from different political leanings and even countries to catch stories and viewpoints that some outlets may cover while others ignore.

In an age of deep polarization, many people claim to “just want the facts,” “follow the science,” or “read only unbiased news sources.” These statements suggest a belief in the possibility of pure objectivity—a clear, unbiased view of reality. However, for humans, true objectivity and wholly objective news or other information sources do not exist.

Human beings are not neutral observers of the world. We filter what we see, hear, and believe through perception, memory, emotion, and cultural layers. While objectivity is a valuable ideal, cognitive and neuroscience science reveal that the human mind is wired in ways that make objectivity elusive.

The Brain is a Meaning-Making Machine

Perception is not passive. Our brains do not simply record sensory information like a video camera. Instead, they interpret, select, and organize raw data to create a coherent narrative. This process is influenced by attention, past experiences, emotional states, and expectations.

Studies in psychology have shown that people can literally see the same event differently depending on their beliefs or social affiliations—a phenomenon known as motivated perception. In one classic experiment, students from rival schools were shown the same football game, yet each group believed the opposing team had committed more fouls. The visual data was identical, but the interpretations diverged dramatically.

This highlights a key point: our brains are not built for objectivity—they are built for meaning. We naturally filter information through cognitive and emotional frameworks that help us make sense of a complex world.

Cognitive Biases: The Invisible Filters

Over the past several decades, psychologists have identified a host of cognitive biases that shape how we perceive truth. These biases operate automatically and unconsciously. Even well-intentioned, intelligent individuals fall prey to them. This isn’t a moral failing—it’s a function of how the brain works.

In other words, we don’t simply have biases—we are biased by nature. Objectivity, then, isn't our default mode but a disciplined exception.

Culture and Language as Lenses

Beyond individual psychology, culture adds another layer of influence. We do not think in a cultural vacuum. Language, norms, values, and shared narratives shape what we consider true, important, or even thinkable.

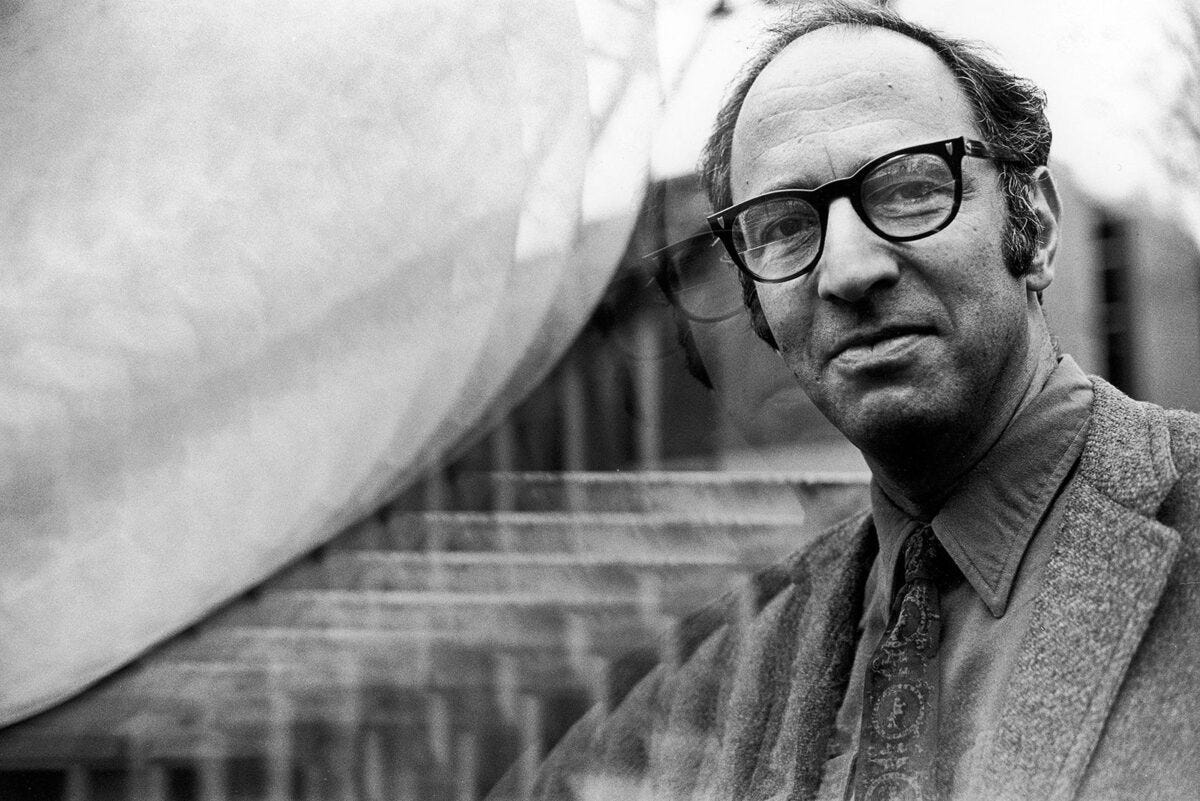

The Harvard University philosopher and historian of science Thomas Kuhn famously argued that scientific paradigms themselves are culturally situated—that scientists working within one paradigm literally "see" data differently than those in another. The implications are profound: even in the most rational, empirical domains, perception and interpretation are shaped by social context and subjective human beings.

This doesn’t mean that truth is purely relative, but it says that our access to truth is mediated by the lenses we inherit and often do not notice.

Striving for Objectivity in an Unobjective Mind

So if pure objectivity is impossible, should we give up on the idea entirely? Not at all. In fact, recognizing our biases is the first step toward better thinking.

Critical thinking, open dialogue, diverse perspectives, and empirical methods exist precisely because we are biased. These tools help us approximate objectivity—not by removing human subjectivity, but by counterbalancing it.

Science, for instance, relies on peer review, replication, and falsifiability not because scientists are perfectly objective, but because they are not. These institutional practices exist to guard against error, distortion, and self-deception.

Similarly, seeking out dissenting and unfamiliar voices, and news and other information sources from a diversity of political and ideological perspectives, isn’t a sign of weakness—it’s a strategy for getting closer to the truth.