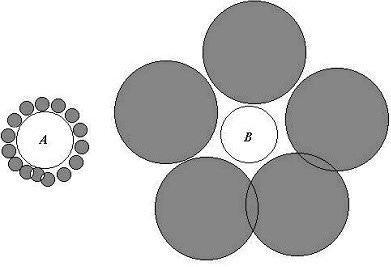

Human perception of objects is influenced by nearby objects, qualities, and other information. Both consciously and nonconsciously we judge things through comparison. This regularly leads to misperceptions and misidentifications.

To measure fabric, you use a yardstick for comparison. To assess someone's hand size, you might place your palm next to theirs. To judge someone's speed, you could race them or watch them compete against someone else.

In less precise comparisons, humans evaluate length, height, angle, shape, color, and distance by comparing objects within a scene. For example, when looking at a family photo, you might estimate the height of a stranger by comparing them to someone you know. You could gauge the distance to a house by comparing its size to that of nearby buildings and trees. You might estimate an angle by comparing it to a level line (e.g., "It looks about 10-15% off from level").

These estimates are often reasonably accurate. You might guess that the stranger in the photo is 6 feet tall, knowing your aunt is 5'5". When you meet him, you may find he's actually 5'10-1/2". While not perfect, it's a very close guess—especially since you couldn’t see the shoes they were wearing.

However, while comparing objects is crucial for making judgments, it can also lead to errors. Seemingly logical comparisons can result in surprisingly incorrect conclusions. These errors arise when our assumptions about an object or the entire scene are flawed.

For instance, what if you mistakenly remembered your aunt as 6 feet tall instead of 5'5", since the last time you saw her you were a 5-year-old? Your height estimate for the man would be similarly off. You might guess he was 6'7". What if your aunt was wearing flats in the photo, while the man, self-conscious about his height, was wearing lifts? And what if the man couldn’t make the family reunion, and a cousin digitally inserted his image into the picture?

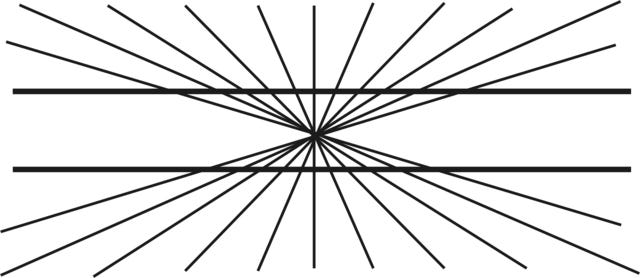

The above two horizontal lines are straight and parallel. The angled background makes them appear to bend. Without the angled background, the lines would appear parallel.

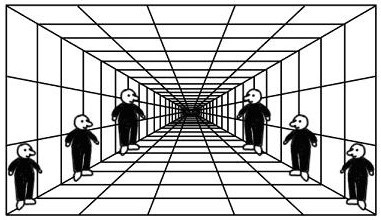

In the above, the men are the same size. Measure them yourself. It is the skewed diminishing scale lines that make them appear to be of different sizes.

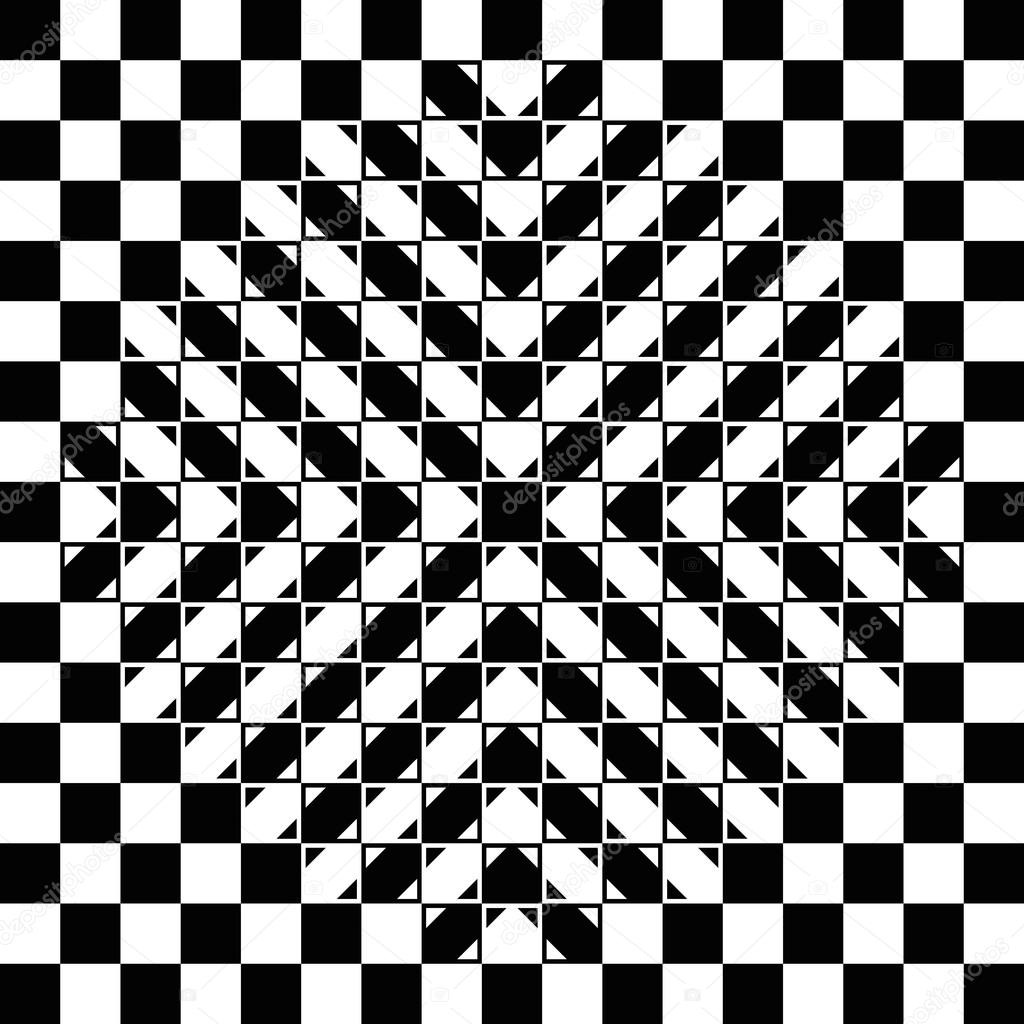

There is no bulge in the above checkerboard. The horizontal and vertical lines are perfectly square and even. It is the triangles in the corners of the middle squares that make it appear to bulge.

.

Camouflage: Seeing But Not Perceiving

With some forms of camouflage, such as a brown chameleon standing in front of a matching brown rock, you see the chameleon but don't perceive it. Your eyes and mind receive the same visual chameleon information as when the chameleon is standing in front of a white sheet. This is how a chameleon or an arctic fox can hide in open view.

.

Questions

Does all human perception require comparison and contrast? How about all human thinking and ideas? Can a human perceive a color without contrast and comparison, including mental & memory comparison?

How does one’s education, experience, and culture play into comparison and identification?

Hofstadter’s book “Surfacers and Essences” makes a compelling case that analogy (comparisons) is the foundational process of thinking. https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/7711871-surfaces-and-essences