Throughout history, depictions of Jesus Christ have taken on a remarkable diversity of racial and cultural forms.

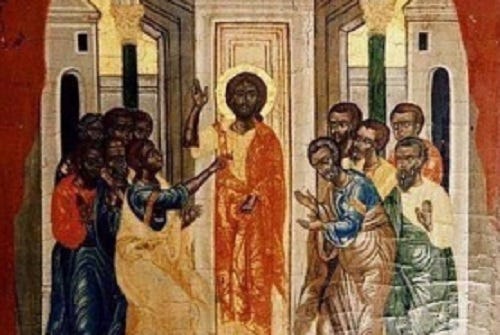

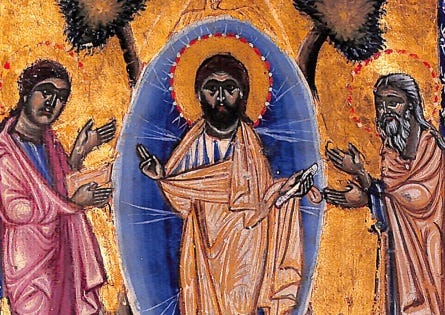

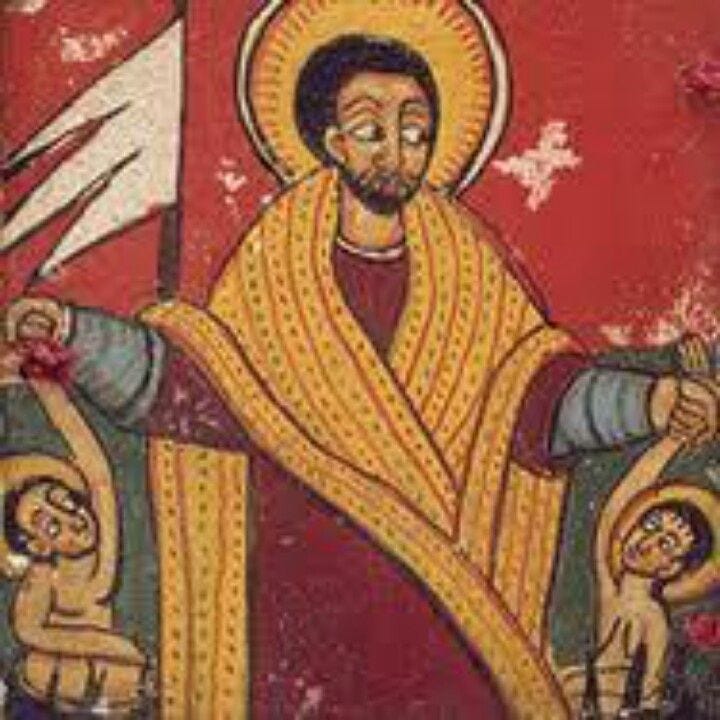

In Western European paintings, Christ often appears with pale skin, light brown or blond hair, and distinctly European features. In Ethiopian Orthodox icons, he is African. In Latin American murals, he may be depicted with brown skin and native clothing, while in East Asian Christian art, he is shown with local facial characteristics and fashion.

These differences are not merely artistic liberties—they reflect how religious imagery operates within particular cultural, political, and theological contexts.

Jesus of Nazareth was a historical figure: a Jewish man born in first-century Roman-occupied what is now Israel. No one is certain what he looked like, though he likely had olive-toned skin, dark hair, and Semitic facial features common to the region.

Yet Christian art has rarely aimed for strict historical realism. Instead, it has prioritized symbolic meaning, emotional resonance, and cultural familiarity. Across time and place, Christian communities have adapted Jesus’s image to reflect themselves, to inspire identification, and to communicate spiritual truths in relatable ways.

As Christianity spread from the Middle East into Europe and beyond, depictions of Christ began to align with dominant cultural aesthetics. By the Middle Ages and Renaissance, European artists had standardized a white, European-looking Jesus. This image became not only familiar but authoritative, reinforcing the cultural identity of European Christians and, later, aiding in the religious and political agendas of European colonial powers. During colonial expansion, missionaries carried this version of Jesus to the Americas, Africa, and Asia, where it became entrenched as a symbol of both Christian doctrine and Western dominance.

In more recent centuries, however, many Christian communities have reimagined Christ in their own image.

These depictions are not attempts to assert the historical appearance of Jesus, but to make theological and cultural statements. Ultimately, Jesus functions as a theological metaphor, symbol, and teaching aid.

Theologically, many Christian traditions support this diversity. The Catholic Church teaches that Jesus Christ is the visible image of the invisible God and the perfect reflection of humanity made in God’s image. As such, Jesus represents not just one people, but all of humanity. Catholic theology embraces the principle of inculturation—the adaptation of Christian teachings, symbols, and imagery to different cultural contexts. The Second Vatican Council emphasized the need for the Church to communicate in the “language of the people,” which includes visual and symbolic forms. As a result, Catholic communities around the world are encouraged to depict Christ in ways that reflect their own ethnic and cultural identities, reinforcing the universal accessibility of divine grace.

I remember Sister Aurea, my 6th, 7th and 8th grade Benedictine nun teacher at a Catholic school 1959-1962), telling us that, given his time and location, Jesus was definitely at least brown, probably dark brown, possibly Black. Therefore, she asserted, no Christian should ever be racist regarding race or ethnicity. On the other hand, she also taught us that it was a sin to be curious about other religions. She told us that if we needed to attend another church for a wedding or a funeral, for example, we should attend only physically and not engage with the religious part mentally or emotionally.

I wonder what Jesus might have looked like if he had been a typical, average human. Perhaps AI could generate what the generic human male would look like, a mix of all the races.