Steven Levitt and the Myths of Conventional Wisdom

The world is full of hidden incentives that shape behavior

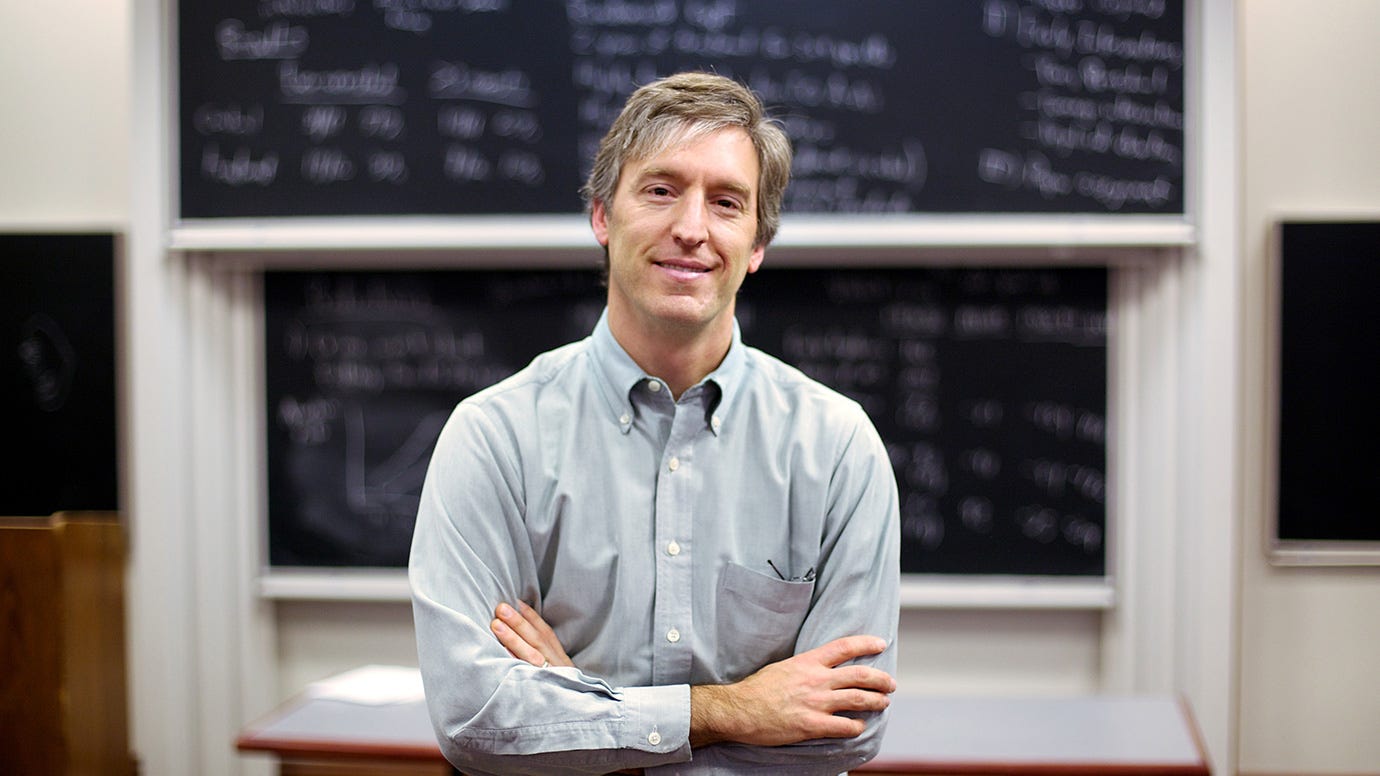

When most people think of economics, they picture Wall Street, interest rates, and government budgets. Steven Levitt, an economist at the University of Chicago, changed that image. He showed the public that economics is really about incentives, the hidden forces that shape what people do.

Levitt’s main idea is simple. Conventional wisdom is often wrong. What “everyone knows” is usually based on habit, bias, and convenience. To find the truth, we have to question our assumptions and look at the data.

Born in Boston, Levitt studied economics at Harvard and earned his Ph.D. at MIT. His early research looked at unusual topics such as corruption in sumo wrestling. When he joined the University of Chicago, he stood out for studying real-world questions instead of abstract theory. His mix of curiosity and careful analysis later made his book Freakonomics a global bestseller.

Levitt’s method is clear. Take a common belief, ask an unexpected question, and test it with data. The answers often surprise people.

Take the housing market. Most assume real estate agents want to get the highest price for your home. Levitt found that is not always true. Because agents earn only a small fraction of the sale price, it is in their interest to sell quickly, even if waiting could earn the homeowner more. The incentive structure pushes agents toward fast sales, not better ones that take more time and work.

He found similar patterns in medicine. Doctors seem purely focused on patient care, yet financial incentives sometimes encourage unnecessary procedures. A surgeon paid per operation has a motive to perform more surgeries, even when other treatments might work.

One of Levitt’s most debated findings explains why crime dropped in the United States the 1990s. Many credited policing and tougher laws. Levitt found another factor: the legalization of abortion two decades earlier. Fewer unwanted children meant fewer people growing up in high-risk environments. By the 1990s, crime declined. The claim was controversial, but it showed Levitt’s commitment to following the data wherever it led.

Education offered another example. Teachers want students to learn, but when test scores determine job security, some cheat by altering answers. Levitt found clear patterns of this behavior in the Chicago public school system. The problem was not bad teachers, but counterproductive incentives.

Levitt also showed how people misjudge risk. Ask parents which is more dangerous for a child, a home with a gun or a swimming pool, and most say the gun. Yet, data shows that a child is about a hundred times more likely to drown in the pool than to die from a gun. The point is not that guns are safe, but that our fears are often irrational, not logical. We worry about dramatic dangers and ignore everyday ones.

Across all his work, the message is the same. The world is full of hidden incentives that shape behavior.

Levitt’s lesson is not to be cynical, but curious. Question your assumptions and what everyone takes for granted. Look for the motives behind actions. Let evidence, not opinion or ideology, guide your thinking.