The Many Problems with “Words Are Violence” and “Silence Is Violence”

The Dangers of Equating Words with Violence

I begin by making it clear that I do not support hateful language. I believe in listening and being considerate to others, and avoiding logical fallacies, including ad hominem attacks.

At the same time, I support freedom of speech, honest debate, and the open exchange of ideas. No side holds a monopoly on truth, and those we disagree with can offer us valuable insights and information, including about ourselves.

.

In recent years, the slogans “words are violence” and “silence is violence” have become common in progressive identity politics social justice activist and academic settings. They are meant to express that speech can cause harm and that staying silent about injustice effectively makes one a supporter of the injustice.

However, when taken literally and used dogmatically, they create serious problems. They blur the difference between speech and physical aggression, promote censorship, discourage emotional resilience and critical thinking, and can even justify real-life physical violence.

When People Mean It Literally

As with other slogans, many people use the phrase “words are violence” metaphorically. However, many activists, especially those influenced by postmodern critical theory, mean it literally.

In Excitable Speech (1997), postmodernist philosopher Judith Butler argued that slurs and hate speech don’t just describe harm, they produce it by reinforcing oppression.

This idea now influences some universities and activist movements, where “hate speech,” which extreme social justice ideologues apply to dissenting opinion and even the expression of ideologically inconvenient facts, is treated as an actual act of violence rather than offensive speech. As one frustrated observer of this trend put it:

“It’s getting to the point where I am so sick of the phrase ‘literal violence.’ I am so sick of people quoting the dictionary or being blunt about scientific facts and then being accused of ‘literal violence.’”

Words Are Not the Same as Violence, and Thinking That They Are Is Bad for Mental Health

Equating words with violence is one thing when used as a metaphor, but it is absurd when seen as a literal truth. Clinical psychologist Chloe Carmichael says that believing words are actual violence— not as in the metaphorical “his words were like a slap in my face,” but as “his words were a literal slap in my face”— is borderline “psychotic.”

Psychiatrists and psychologists warn that treating words as violence is bad for mental health. Michael Ziffra, a psychiatry professor at Northwestern University who specializes in anxiety disorders, writes:

“When you label political speech as ‘violence,’ you harm your emotional well-being by encouraging a victim mindset. You learn to see anger or anxiety as fully justified rather than as something to manage. Predictably, a vicious cycle emerges. When you start to identify yourself as a victim and label uncomfortable speech as violence, this shapes how you view any future experience in which you encounter words or ideas with which you disagree. You will be primed to regularly see ‘violence’ in everyday speech and develop intense negative emotions in response to this perceived violence.

There is another serious implication of labeling speech as violence. It inappropriately shifts the responsibility in terms of who you see as being accountable for managing your emotions.”

Carmichael, who also specializes in anxiety disorders, makes a similar point:

“Confusing metaphorical with literal violence reflects a deeply unhealthy mindset that blurs the distinction between emotional and physical reality. Overpathologizing normal everyday struggles—such as calling words ‘violence’—creates a victim mentality and makes people less resilient. It also discourages open communication, as people become afraid to speak honestly.

Words can sting, but they are not the same as physical harm. Equating speech with violence not only inflates anxiety but also undermines resilience. It conditions people to believe that discomfort is intolerable and that retaliation—even violent retaliation—is justified. By contrast, protecting free speech fosters self-efficacy—the belief in one’s ability to navigate challenges constructively. It strengthens authentic connection, reduces the loneliness that comes from self-censorship, and creates opportunities for genuine problem-solving.”

Jonathan Haidt, a New York University social psychology professor and author of the books The Coddling of the American Mind and The Anxious Generation, says it is bad for students’ intellectual and emotional health to teach them to catastrophize and see everything as a danger. It sets them up for failure in the real world, where they will encounter people with different beliefs and who disagree with them.

Black scholars John McWhorter and Glenn Loury argue that while these ideas are intended to protect minorities, they instead disempower and infantilize them, condescendingly treating them as fragile, lesser, and perpetual victims. Loury, a Brown University economics professor and author of The Anatomy of Racial Inequality, calls this mindset “a secularized version of the white man’s burden”—the notion that minorities need protection rather than freedom.

How It Undermines Critical Thinking, Learning, and Discussion

Critical thinking depends on separating emotion from reason and weighing arguments based on evidence. The idea that “words are violence” undermines this by teaching that disagreement is dangerous, that anyone who disagrees is inherently morally suspect, and that hearing an opposing view is a form of harm. This belief is coupled with other illiberal postmodern activist theories that treat free speech as oppressive and that platforming viewpoint diversity is dangerous.

Greg Lukianoff, a constitutional lawyer specializing in the First Amendment, explains that the claim that words are violent is often used as a political tactic to shut down and demonize disagreement. He writes:

“It’s a tactical advantage when facing any speaker you hate. Equating words and violence is a rhetorical escalation designed to protect an all-too-human preference which Nat Hentoff used to call ‘free speech for me, but not for thee.’”

It Dilutes the Meaning and Power of Words

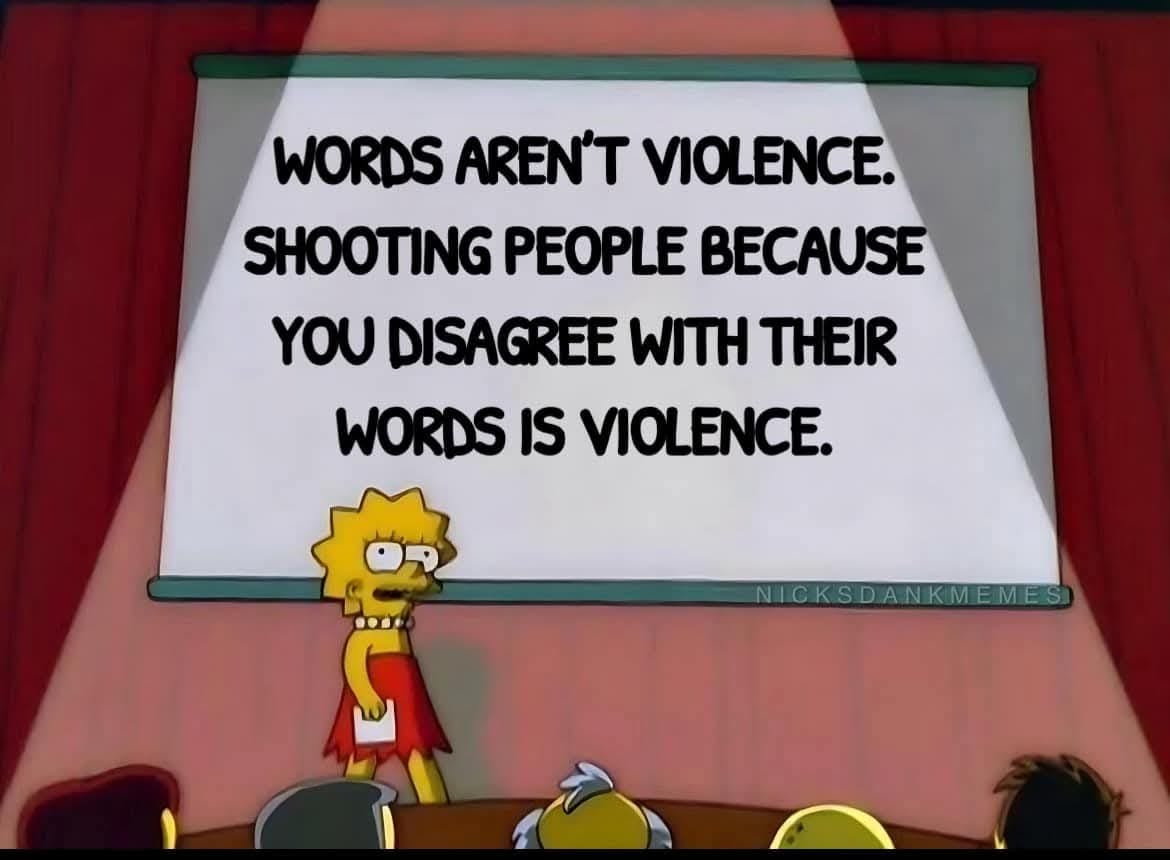

Calling words “violence” distorts and weakens the meaning of the term. Real violence causes physical harm. It breaks bones and ends lives. Words can hurt emotionally, but they do not physically injure people.

When every rude remark is labeled “abuse,” every disagreement is “harm,” and every controversial idea is “hate speech,” the words lose meaning. When real acts of brutality and hatred end up treated as no worse than a harsh opinion or a tweet, the words are no longer taken seriously.

The same inflation happens with words like racism, white supremacy, and transphobia. The once clear terms racism and white supremacy have been stretched by activists to cover almost anything, from Robert’s Rules of Order and punctuality to spelling standards. Transphobia is even used against people, including transgender people, who support trans rights but question certain activist claims or methods. This misuse drains the words of power and distracts from real cases of bigotry.

Much of the public no longer takes these terms seriously, not only because of this dilution, but because they’ve watched them lose their original common sense and commonly understood meanings and become partisan tools for enforcing political and ideological conformity.

When “Words Are Violence” Leads to Real Violence

If people believe words are a form of violence and that people with different viewpoints are a physical danger, then physical violence can start to seem like self-defense. McWhorter warns that “if words are violence, then violence becomes an acceptable response to words.” Loury adds that when disagreement is treated as aggression, “you collapse the moral space for dialogue. That’s when actual violence becomes thinkable.”

Journalist Matt Taibbi makes a similar point, saying that “if speech is violence, then moral aggression against the speaker becomes peacekeeping.”

This isn’t just theory. It has led to real events. At Middlebury College and the University of California in Berkeley, guest speakers were attacked and shouted down because their ideas were labeled “violent.” Political science professor Allison Stanger was hospitalized after being attacked while trying to escort a controversial guest speaker.

The same reasoning was used to justify the 2015 Charlie Hebdo massacre, the 2022 knife attack of author Salman Rushdie, and the assassination of conservative activist Charlie Kirk during a public political debate. The attackers claimed they were responding to “hate speech.”

Jon Zobenica of the U.S. Free Speech Union writes, “The more we’re encouraged to think of words as violence, the more some among us will come to think of violence as a proportional response to words.”

Too often these days, political opponents aren’t considered as people with different viewpoints but called “evil,” “fascists,” and “Hitler.” Polls have shown that those who demonize their opponents this way are more likely to support undermining democratic processes to punish their opponents, unfair court punishment of their opponents, censorship, and even violence.

“Silence Is Violence”: Another Slogan of Coercion

The related slogan “silence is violence” pressures people to speak up, but only in approved ways. The idea is that being silent in moments of injustice only serves to support the injustice. However, when these activists insist you speak up, they insist you speak up in exact agreement with them, using their jargon and theories. Speaking up with different viewpoints will be attacked and called “violence.” This is compelled speech.

How These Ideas Undercut the Movement

Strident efforts to control language and punish dissent inevitably backfire. They make movements look extreme, intolerant, and authoritarian, alienating not only most of the public but driving away even many supporters.

Further, absurd claims and Orwellian slogans—such as that math and logic are racist, science and freedom of speech are oppressive, words are literal violence, and whatever a minority says must be accepted as unquestionable truth— make a movement appear to most of the public to be unreasonable and deluded. Many prominent Democratic Party leaders themselves, including Barack Obama, James Clyburn, and Karen Bass, said that the only thing the activist slogan “Defund the Police” achieved was to get more Republicans elected.

References and Further Reading

“Why It’s a Bad Idea to Tell Students Words Are Violence” by Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff

“Why the ‘words are violence’ argument needs to die” by Greg Lukianoff

“No, Words Are Not Violence” by Michael Ziffra, MD

“Words Are Not Violence And Here’s Why That Matters” by Chloe Carmichael, Ph.D.

This (silence is violence) is why I left. They redefined my speech disorder into a form of violence, and scared me to death. They pretended to be scared of my muteness and disjointed speaking to treat me as a physical threat until I resigned because there was nothing I could do without risking my life or freedom. They also probably compelled me to speak more than I should have because they were very scared of my silence. I tried so many times to explain my disorder, but each time I would still be yelled at or treated like a threat for being too quiet or using the wrong words.

They were attacking me for being disabled, something that I have had to work hard at to overcome. Once I fully realized what they were doing, I could resign safely.

Recent tragic events confirmed the paranoia I was feeling then was not all in my head.

Absolutely right. Redefining words so drastically also wrecks communication. And "violence" is just one example of this. "White supremacy" culture, only whites can be "racist," etc. Always reminds me of "War is peace, freedom is slavery, ignorance is strength"....