The positives and negatives of identity politics

Progressive identity politics has emerged as a dominant and divisive force in politics and social activism

In recent decades, progressive and postmodernist identity politics has emerged as a dominant force in political discourse and social activism. Rooted in the experiences of minority groups, identity politics emphasizes the importance of collective identity in the pursuit of justice and equality. At the same time, it has been criticized for creating division, alienation, and polarization, and reinforcing racial, ethnic and other stereotypes.

At its core, identity politics is a response to the human need for belonging and recognition. Psychologically, our identities—whether based on race, gender, religion, or other factors—play a critical role in shaping our sense of self and our interactions with the world. According to social identity theory, people derive a significant portion of their self-esteem from their group memberships. This creates a natural tendency to seek solidarity with those who share similar experiences and to advocate for the interests of one’s group.

For minority groups, collective identity becomes a source of power and resistance against oppression. However, identity politics often amplifies in-group and out-group dynamics. While this can foster solidarity within minority communities, it can also lead to stereotyping, prejudice, and conflict between groups. Additionally, cognitive biases such as confirmation bias and motivated reasoning can reinforce identity-based perspectives, making it difficult to engage constructively with opposing viewpoints.

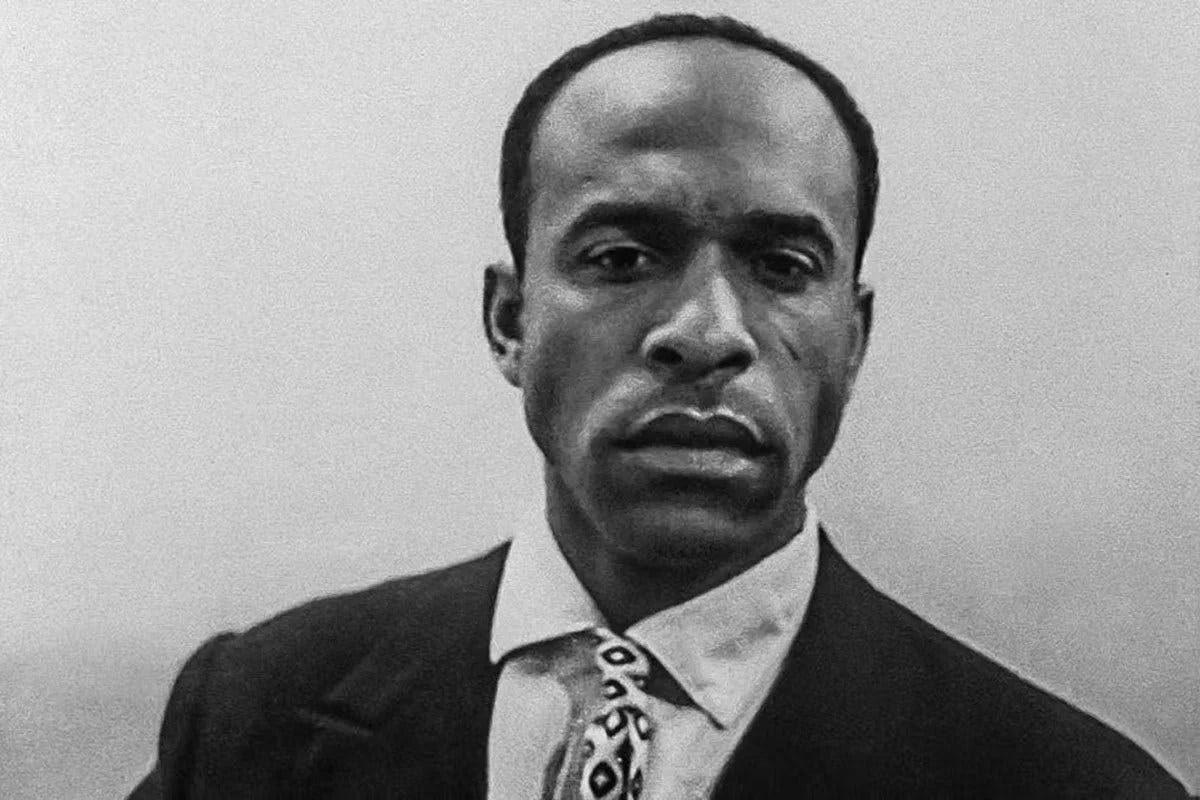

Philosophically, identity politics draws on theories of justice, recognition, and power dynamics. Influential thinkers such as Frantz Fanon, a French philosopher, Kimberlé Crenshaw, an American law professor, and Charles Taylor, a Canadian political philosopher, explored the role of identity in both personal liberation and social change.

Taylor argues that recognition is a fundamental human need. Denial of recognition—through misrepresentation and marginalization—constitutes a form of oppression. Identity politics seeks to address this by asserting the value and dignity of minority identities, challenging dominant narratives, and demanding equal representation.

Crenshaw’s concept of intersectionality highlights how overlapping systems of oppression (e.g., racism, sexism, classism) create unique experiences for people at the intersection of multiple minority identities. By focusing on intersectionality, identity politics aims to address the complexities of inequality and ensure that no one is left behind.

Further, proponents of progressive identity politics critique traditional political theories that emphasize universal principles such as equality and individual rights, arguing that these frameworks can overlook the specific needs and experiences of minorities.

When grounded in the pursuit of justice and equality, identity politics can be a powerful tool for social change. By affirming the value of minorities identities, identity politics fosters empowerment, pride, and resilience among those who have historically been excluded or oppressed. Movements such as Black Lives Matter and LGBTQ+ rights have mobilized identity politics to achieve significant legal and cultural advancements.

Identity politics also highlights the structural and institutional barriers that perpetuate inequality. By focusing on the opinions and experiences of those most affected, it drives reforms that address these issues. Additionally, efforts to increase representation in media, politics, and other spheres of influence ensure that diverse perspectives are heard and valued.

Despite its positive potential, identity politics has dangers. A focus on identity can exacerbate group divisions, create tribalism, and foster an "us vs. them" mentality that hinders constructive dialogue and cooperation. In extreme cases, it can provoke resentment or backlash from those who feel excluded or threatened by identity-based movements.

Critics argue that identity politics can oversimplify complex individuals by reducing them to their group affiliations. This essentialism risks reinforcing stereotypes and prejudices and ignoring intragroup diversity. Some racial and ethnic minorities have been some of the biggest critics of identity politics and its tendency to group and weigh people by their immutable characteristics.

Glenn Loury, a black economics professor, says the “BIPOC” and “white” racial categories arbitrarily group together people of wildly diverse experiences and views. Irshad Manji, a Ugandan-Canadian educator and author, says that critical race theory boxes people into simplistic categories and hinders understanding and empathy between identity groups. David Bernstein, Director of the Jewish Institute for Liberal Values, argues that critical race theory’s categorizing of Jews as “privileged whites” reinforces age-old antisemitic tropes and dismisses Jews’ complex experiences in the United States. He further writes that progressive postmodernist identity politics undermines vital Western Enlightenment ideals such as science, mathematics, reason, freedom of belief and speech, and meritocracy. Coleman Hughes, a black philosopher and political theorist, argues that society should be moving away from racial, ethnic, and other caste systems rather than creating new ones.

Moreover, some say that identity politics fragments political movements by prioritizing narrow group interests over broader, universal goals. This makes it harder to build coalitions and achieve widespread change. Black studies professor and social activist Findley Campbell argued that progressive racial identity politics divides the American working class and poor, pitting against each other people who should unite in shared economic interests.

Identity politics, of course, is not only a thing of the political left. We all associate ourselves with particular groups. Identity politics in the political right is also a double-edged sword, at times promoting healthy patriotism and group pride while at other times perpetuating racial and ethnic bigotry and xenophobia.

In summary, identity politics is a complex and multifaceted force that can be positive and negative. Leftist identity politics has empowered minority groups,and driven meaningful reforms, but at times creates division, oversimplification, and polarization. Striking a balance between advocating for specific identities and pursuing broader goals of unity and universal principles is a challenge. In both the left and the right, identity politics reflects the universal human need for belonging but must be approached carefully to promote constructive dialogue and meaningful progress without becoming a solution that worsens the problems.

This is a very well-written, brief article! Thanks!

I've noticed that those who talk of "identity" will often change their tune when they encounter an identity group or demographic (racial or religious, for example) that they don't like. Also, we need to remember that patterns of choice, action, and behavior, are -by definition -open to the making of moral or value judgments. Moral standards are, inherently, discriminatory -differentiating between various choices and actions. People have the right to make such judgments, and religious communities are within their rights to express and uphold such standards publicly.