Why does a Roman statue still captivate us? Why do paintings by Vermeer or Hokusai, created centuries ago in vastly different cultural contexts, continue to move viewers today? While tastes in art inevitably shift over time and across cultures, certain works seem to possess a lasting aesthetic appeal that transcends the ages. This raises a fascinating question: What makes some art feel timeless?

The answer lies at the intersection of art history, psychology, and cognitive and neuro science. While cultural trends certainly influence artistic judgment, there appear to be some cognitive and perceptual patterns that give certain artworks enduring power. These patterns are deeply rooted in how the human mind processes visual information, perceives beauty, and finds meaning.

Universal Patterns and Visual Perception

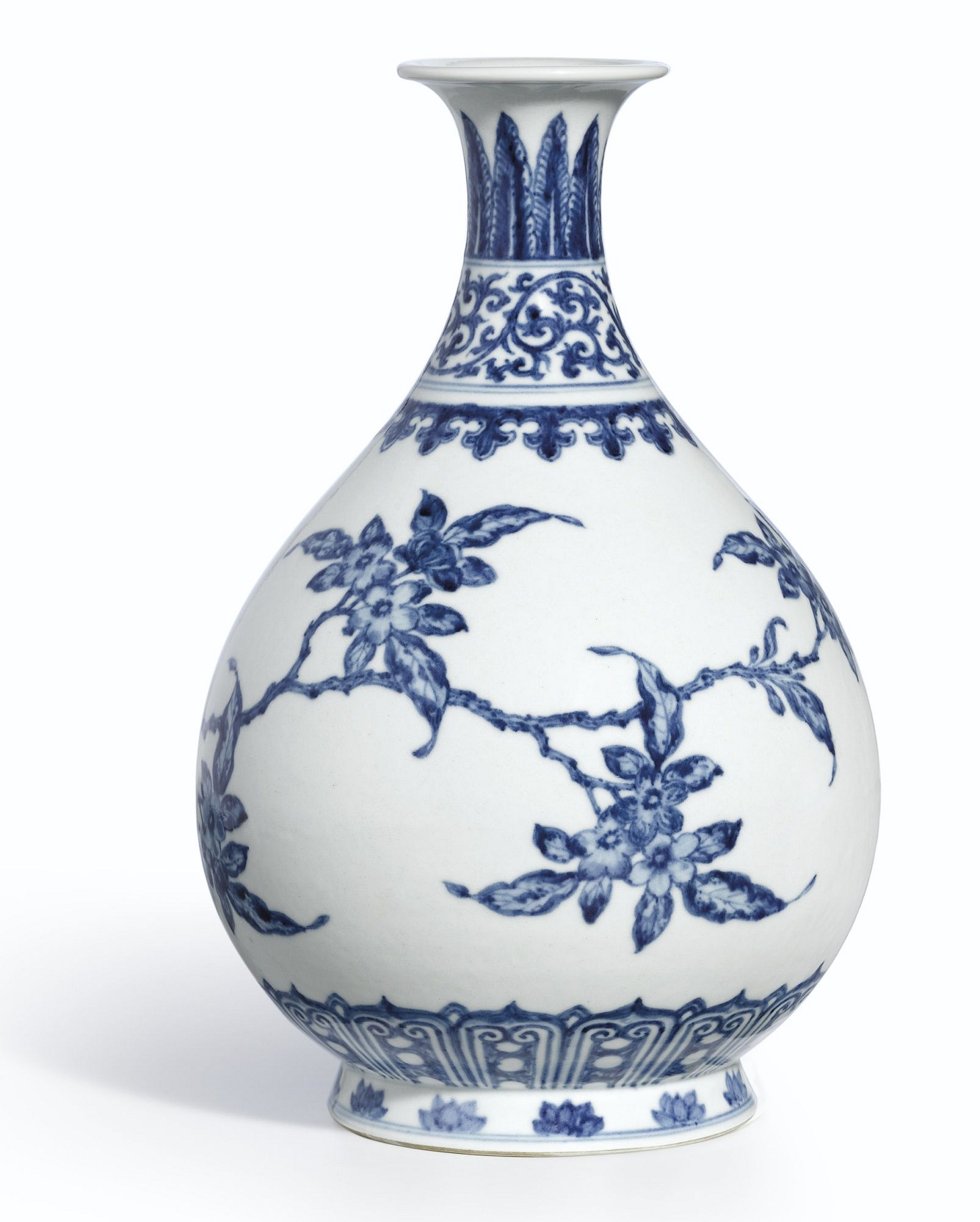

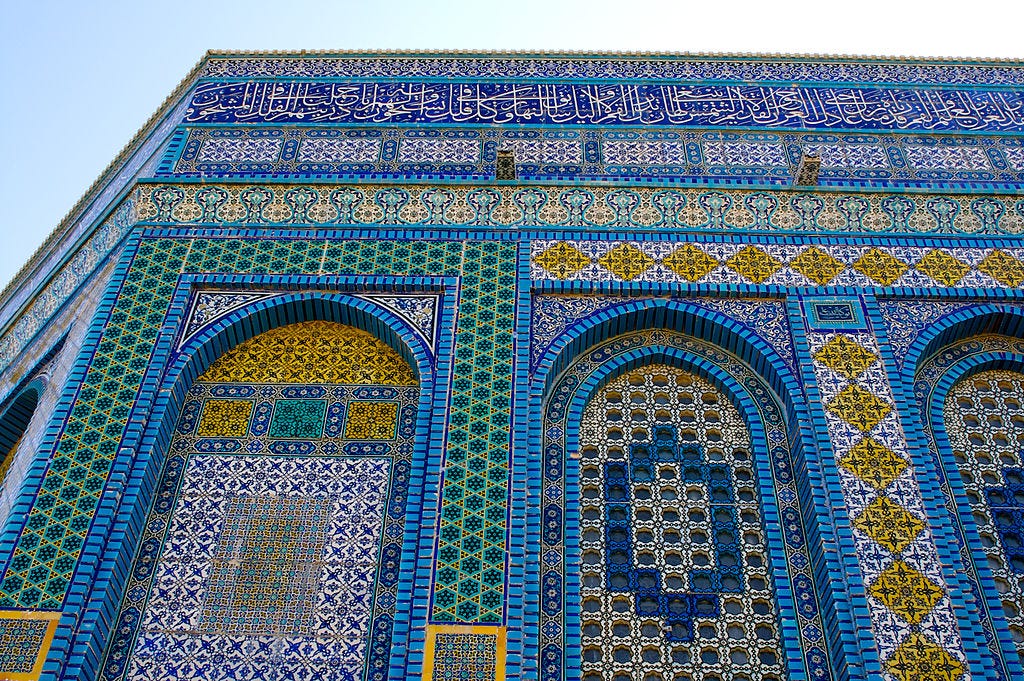

One explanation for the timelessness of certain artworks lies in shared aspects of human visual perception. The human visual system is biologically tuned to respond to specific visual cues—symmetry, contrast, rhythm, and balance among them. These principles are found not only in traditional European painting but in the decorative arts of Africa, Islamic architecture, Japanese prints, and many other traditions.

Artists who tap into these innate visual tendencies often create works that are easy to process and pleasurable to the brain. The psychologist Rudolf Arnheim described this in his theory of visual thinking, suggesting that we do not merely see shapes and colors but actively seek out structure, balance, and order.

The use of the “Golden Ratio” in ancient Greek architecture and Renaissance painting may reflect this appeal. Though the aesthetic status of the Golden Ratio is debated, it points to a broader truth: certain proportions and patterns resonate with our cognitive processing in ways that feel intuitively "right" or beautiful.

Emotional Resonance and Mirror Neurons

Another key factor in timeless art is emotional resonance. Neuroscience suggests that when we see a depiction of emotion—a grieving figure, a joyful dance—our brains partially simulate that emotion through a system of mirror neurons. This allows us to empathize across time and cultural boundaries.

Consider the expressive sorrow of Michelangelo’s Pietà or the quiet domesticity of a Vermeer interior. These works speak to universal human experiences: love, loss, solitude, tenderness. While fashion and politics change, the fundamental emotional range of the human condition does not. Great artists know how to communicate these emotions in visual form, often bypassing language and cultural specifics to connect with viewers on a deeper level.

Meaning and Ambiguity

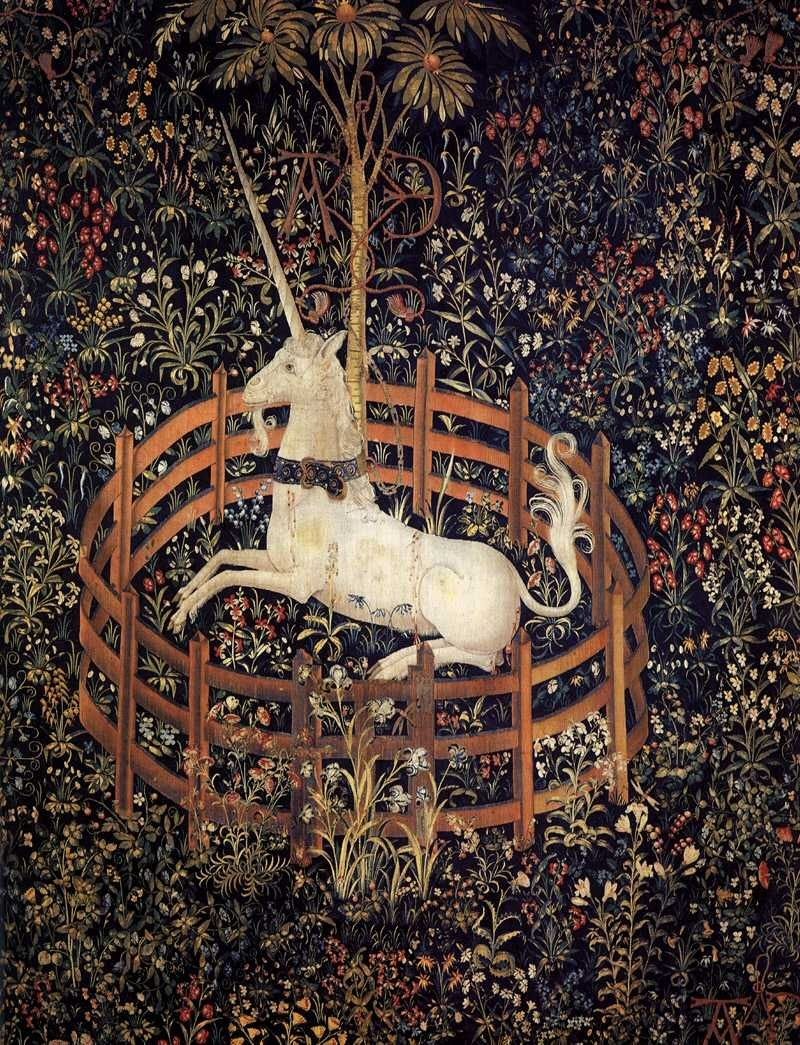

Ironically, one of the qualities that can make art last is its ambiguity. Rather than telling a fixed story, great artworks often open themselves to interpretation. They provoke questions rather than providing answers.

This cognitive openness allows viewers from different backgrounds and eras to project their meanings onto the work. A painting by Caspar David Friedrich may evoke religious awe in one viewer, existential solitude in another, and simply the beauty of nature in a third. This multiplicity makes the work relevant to each generation.

Philosopher Umberto Eco described this as the “open work”—art that invites active interpretation. This aligns with psychological models of perception, which suggest that we don't passively absorb art but actively construct its meaning in our minds.

Cultural Endurance and Transmission

Of course, we must also consider how "timelessness" is socially constructed. Some artworks are preserved, studied, and canonized while others are lost or ignored. Institutions like museums, schools, and critics shape what is remembered.

Yet even accounting for cultural gatekeeping, some works maintain emotional and perceptual impact far beyond their cultural context. Buddhist sculptures from India, Aboriginal cave art, or Mayan carvings can profoundly move viewers with no connection to the originating culture. This suggests that while social transmission matters, some core human cognitive and emotional structures also play a role in artistic endurance.

The Brain as Co-Author

Timeless art, then, is not just about the artist’s skill or the historical moment—it is also about us, the viewers. Our brains, shaped by evolution and culture, help determine which forms resonate and why. Great artists often intuitively understand this. They create works that align with how we see, feel, and make meaning.

The allure of timeless art challenges our common belief in the linear progress of culture and knowledge. Many people assume that, as societies advance, so too does their artistic output—implying that contemporary art is inherently more sophisticated or engaging than that of earlier eras. Yet, the enduring appeal of works like the ancient Greek sculptures, Renaissance paintings, or classical music suggests otherwise. These masterpieces continue to resonate with audiences across centuries and cultures, provoking deep emotional and intellectual responses.

This phenomenon invites us to reconsider what we mean by "progress" in art. While technological advancements and shifting social contexts certainly influence artistic forms and themes, the core human experiences—love, loss, beauty, mortality—remain constant. Timeless art captures these universal truths with such clarity or intensity that it transcends its original context. In this sense, art does not simply "progress" in a linear fashion; rather, it evolves, with each era offering new interpretations and innovations while still drawing from a shared well of human experience.

Moreover, dismissing earlier art as less engaging overlooks the possibility that modern viewers can find fresh meaning in old works. Our changing perspectives may even deepen our appreciation, as we recognize both the differences and the continuities between ourselves and those who came before. Ultimately, the timelessness of art reminds us that cultural progress is not just about moving forward, but also about reaching back and finding connection across the ages.